- Reading

- Concepts

- Learning Objectives

- Questions

- Concept Map

- Summary

- 1. Research methods: What is it? Why does it matter? And how does it relate to statistics?

- 2. Theory: How do I distinguish between a theoretical framework, theoretical explanation, and a hypothesis?

- 3. Variables and Units of Analysis: How do I identify them in a study?

- 4. Dependent, Independent, and Control Variables: How do I distinguish between them?

- 5. Conceptualisation: How do I properly conceptualise a variable?

- 6. How do I properly operationalise a variable?

- 7. How can I tell if a variable is measured as a categorical, binary, ordinal, or continuous (or interval) variable?

Reading |

|

Field, A., Miles, J., and Field, Z. (2012). Discovering statistics using R. Sage publications.

|

Concepts |

|

Research |

Learning Objectives |

|

By the end of this class, students should be able to:

|

Questions |

|

Concept Map |

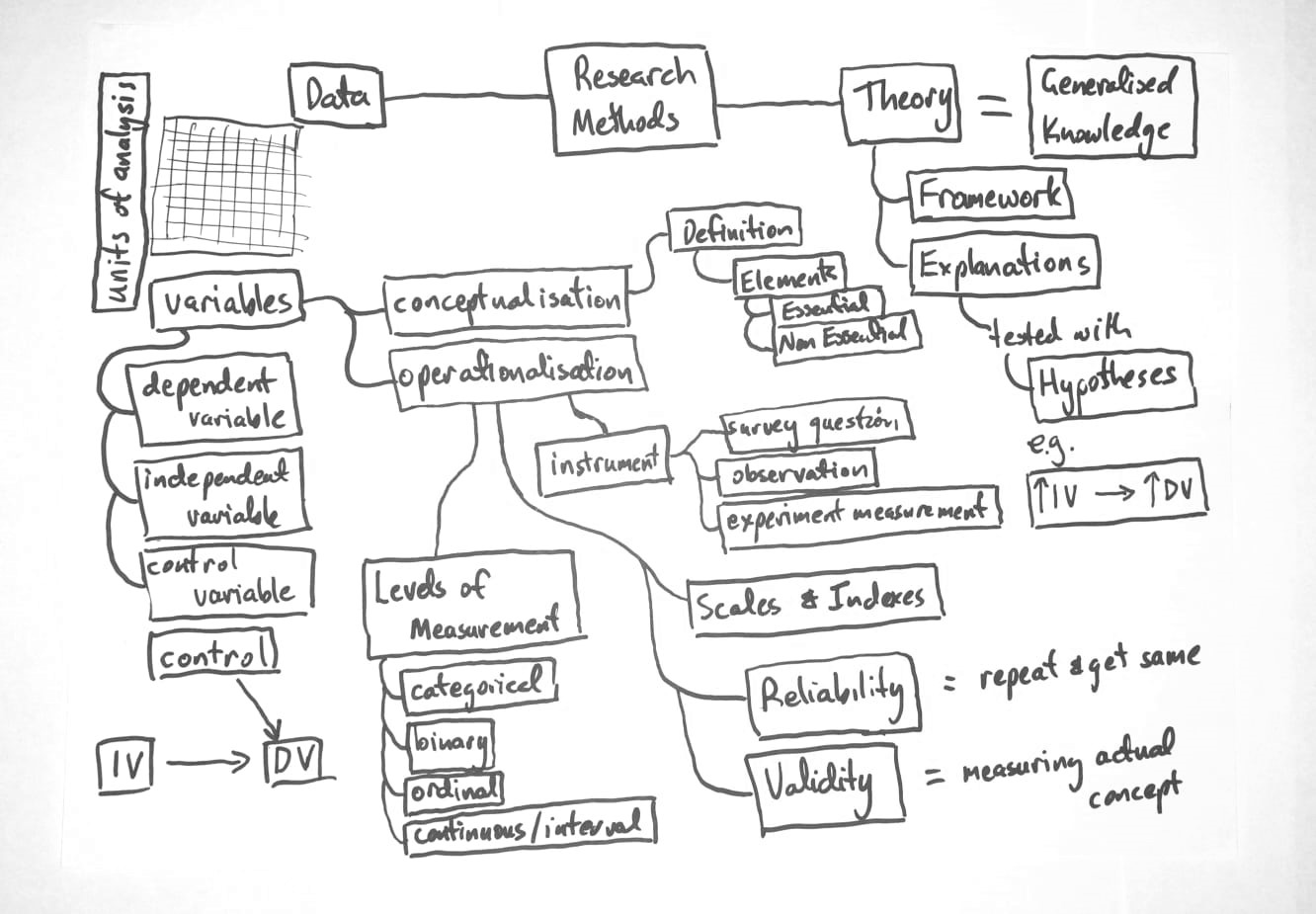

Figure 1: Concept Map of Week 2: Research Methods |

Summary |

|

Testing Theories The main purpose of academic research is to create generalised knowledge: knowledge which provides explanations across more than just the situation, example, or cases being studied. Social scientists develop, discuss, and formalise generalised knowledge through the development and testing of various social theories. These theories are complex abstractions. When social scientists use the word theory they generally mean either (1) frameworks - such as Marxism, functionalism, or rational choice theory - which like religious or political beliefs, are important abstract conceptions of the world, but ultimately are difficult to test. The other meaning of theory is (2) explanations. Explanations provide an account of how or why some outcome occurs. Explanations are distinguished from frameworks by, firstly, focusing on an outcome; and, secondly, containing testable predictions about the observable world. The progress of academic knowledge - generalised knowledge - tends to develop through the contestation of competing explanations (theories). Competing explanations are evaluated by testing hypotheses - statements about what we should find in the observable world - where the explanations make different predictions. Variables For statistical analysis we represent the observable world as a data table with rows and columns. The table is comprised of multiple entities - such as people - and their characteristics - such as their age, gender, or political beliefs. We call the entities being studied units of analysis, and these units of analysis are the rows of the table of data. The characteristics measured on these entities (units of analysis) are called variables (since they vary across units of analysis). In statistical the characteristics (variables) are the columns of the table of data. We distinguish between three main types of variables (i.e. characteristics of our units of analysis) by naming variables according to whether they are ‘causes’, ‘effects’, or ‘other explanations’.

Conceptualisation and Operationalisation To collect data we need to be able to measure the social world. Measurement is said to involve two steps conceptualisation (developing ideas, concepts), and operationalisation (developing measurement instruments). The conceptualisation of a variable is normally captured in a written definition. Definitions are comprised of two main components - essential characteristics and non-essential characteristics. Essential characteristics, as the name implies, are necessary, while non-essential characteristics, are those characteristics often associated with the concept, but not necessary. A useful way to illustrate and highlight the importance of essential characteristics to a definition is to identify examples of the concept with all the essential characteristics, and also non-examples, which are missing just one essential characteristic. Operationalisation involves developing an instrument for measuring your concept (conceptual variable). Social scientists use a wide variety of instruments to measure the real world - survey questions, direct observation, experiments, or counting of words in text. Levels of measurement In statistical analysis, it is an essential requirement that these measurements be transformed into numbers. We talk about (at least) four types of numbers - levels of measurement - in quantitative data collection:

Scales and indexes Measurement can be improved by using multiple instruments or measures for the same conceptual variable. We call a measurement comprised of multiple smaller measurements a scale or an index. Reliability and validity We can test the quality of our measurement by assessing reliability and validity. Reliability is high when a measurement gives the same answer when repeatedly measuring the same ‘thing’. Reliability can be measured with correlations between test and retest on the same subjects, or subjects assessed to have similar values of a variable based on some more strenuous objective assessment (e.g. an examination by a professional). Validity is high when a measure actually measures the concept it says it is measuring. Validity is generally assessed by (1) the judgement of experts; (2) correlation with validated measures; or (3) correlation with expected outcomes. The easiest way for a social scientists to ensure they use reliable and valid measures is to use measures from published studies of other social scientists. |